When I was in Vet School, I had this professor who would occasionally drop the phrase “Don’t buy the big bag of dog food”. He didn’t intend his comment to be insensitive, or EVER used with clients. Instead he employed it as a tool to link specific disease conditions with a prognosis. For the record, his expression had the intended impact.

This came to mind when I was having a conversation with Cathie Coward, the woman who took the photographs of me you might have seen in my posts ‘Function / Form’ and ‘Our Cancer Lexicon’.

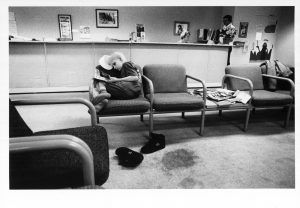

Cathie and I recently got together while I was in Hamilton visiting my family. We hadn’t been in touch for many years, until I emailed her about this SGL blog project. She and I agreed that perhaps some ‘twenty years later’ pictures would be an interesting undertaking, so we spent a day out together, during which I got on a climbing route or two and put myself into a few yoga postures. Cathie also recorded a bunch of audio for an article that was to be published in the Hamilton Spectator.

As a starting point to our conversation Cathie had me flip through Kate’s Story – something I hadn’t done in a very long time. She mentioned a picture I couldn’t recall, from a bone scan that was done around the time I was diagnosed. She recounted showing this image to a physician friend of hers while telling him about the Kate’s Story concept. She told me that when this man saw the image he advised her “don’t get too attached to this little girl…” the human medicine equivalent to “Don’t buy the big bag of dog food”.

I was taken aback when she told me about this conversation, and even more so when I looked again at the image that I hadn’t seen in so long – it clearly shows just how extensive the bone cancer was in my left femur. As a veterinarian today, my interpretation would have been similar to that of the physician back then.

If I think back I can get a handle on the idea that I walked a tenuous line during that period. There were times when I was really sick from the chemotherapy, and I suspect now that the situation was quite precarious.

Unexplainably, back then, the end of my life at a young age never really occurred to me. Though the experience left a lasting impression. Today, I feel acutely aware that, while life is not short, time is indeed quite precious. It makes me tap my one foot when someone is late for a date.

Alright, until next time… For the truly rabid fan-folk, here’s a link to the article I’m talking about and a few recent pictures that didn’t make the cut to the newspaper page.

© Cathie Coward

© Cathie Coward

© Cathie Coward

© Cathie Coward

© Cathie Coward

© Cathie Coward

© Cathie Coward

© Cathie Coward

© Cathie Coward

© Cathie Coward © Cathie Coward

© Cathie Coward