I started climbing about the middle of 2007. I was working in the interior of British Columbia for a brief stint, and started going to a local climbing gym. I then took a two-day ‘Introduction to Outdoor Climbing’ course in Penticton at the end of that summer. After that I moved to Calgary and started hanging around one of the several local climbing gyms there. Same sort of deal as learning any individual sport as an adult – It could as easily have been tennis or golf lessons.

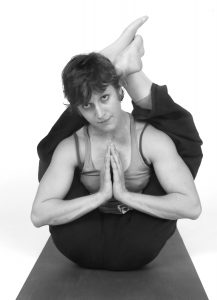

During these beginning phases, I was cramming my walking foot (the plastic one) into a climbing shoe. I know now that a foot designed for climbing is a different thing than a foot designed for walking, but at the time it was the available option. I’d never met anyone without a leg who climbed – I hadn’t met that many climbers, even and I simply assumed I was one of very few… (we prostheletizers can do the ‘assumption thing’ as easily as anyone).

I spent about a year and a half thrashing away, not being able to do much with my leg foot apart from employing it as counter balance and taking small steps onto bookshelf-sized holds. After one particularly frustrating day, I came home and Googled ‘prosthetic climbing foot’, or something similar. One of the top hits I received was a link to a thing called The Eldorado Z-Axis Climbing Foot. Its description mentioned Malcolm Daly and Paradox Sports. I decided to drop Malcolm an enquiring email and his response was to invite me to Ouray, Colorado to go ice climbing. In six weeks. So much for calculated career planning.

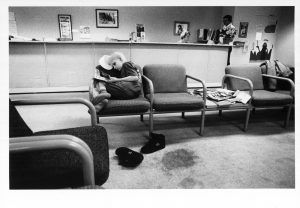

Meeting up with the Paradox crew in Ouray in the spring of 2009 was one of those eye-opening encounters. I think one of the consequences of limb loss due to cancer is that you end up in the ‘cancer crowd’, as opposed to the trauma-leading-to-missing-body-parts-or-loss-of-function crowd. They’re really quite different scenes. The majority of childhood cancer survivors reach the other side with limbs intact, and once you’re over the chemotherapy, I think there’s a tendency to move away from the community, as part of your own recovery process. As a result, I knew very few children without limbs during my cancer treatment days, and none afterwards. I attended one Champs seminar (think weekend health retreat only replace the meditation sessions with artificial limb show and tell), but I think I was too young and wrapped up in the whole treatment process to keep up the connections. By 2009, I was feeling pretty alone with my whole one-legged process.

When I went to Ouray I was all of a sudden immersed in this community of people who climbed, skied, cycled, ice climbed, snow boarded, paddled… They were getting out there. And while some ‘normals’ were invited along for the ride, most Paradoxians were missing something, whether it was a limb, a few fingers, or use of part of their body. Together we climbed frozen waterfalls. We ate. We drank beer out of somebody’s leg. All the usual climbing trip shenanigans.

They’re an inspiring crew. If you ever have the opportunity to go to one of their events I would suggest jumping on it – You’re likely missing more than they are.

© Cathie Coward

© Cathie Coward © Cathie Coward

© Cathie Coward © Cathie Coward

© Cathie Coward © Cathie Coward

© Cathie Coward © Cathie Coward

© Cathie Coward © Cathie Coward

© Cathie Coward © Cathie Coward

© Cathie Coward