C is for Cookie. And catastrophic failure. And Calgary.

Following on from the drama in my last post I feel somewhat obliged to keep the blogosphere in the loop. I started thinking of this next piece right after hitting ‘post’ on “Limb and Life”. Its title was going to be something like ‘What a Difference a Leg Makes’. I do not yet have the material for said piece.

So. Picking up where we left off: My current prosthetist cobbled a temporary leg together, to get me through while we built and tested the next big thing. This short term leg causes less swelling than any other prosthetic has in the last three years, though I wouldn’t call that a sought-after award. But it is enough to get me by, for a while.

After a long wait, the final solution leg I tried two Fridays previous was the culmination of two previous appointments: a casting, followed by a check socket and a second casting. This prosthetic was built with input from a prosthetist in the USA (I had reached out) who has quite a number of LF-toting clients. This prosthetic was to have been ‘The One’. It was not. Not even close – I took it off five hours after leaving the clinic, knowing full well it didn’t fit. Poor LF had ballooned even in those five hours. I had a look, took a deep breath, and went to bed.

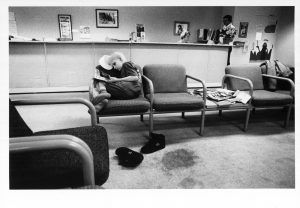

After a fitful sleep I got up early in the morning and had a ‘spiritual awakening’. Which reads far better than ‘had a breakdown’. I called a long-time friend in BC and awakened in his general direction. Another friend was due to pick me up to go climbing. He stopped by and we agreed to meet at the crag. I didn’t say anything about my mood and was tasked with grabbing lunch while he made a quick stop for bolt glue. On my way I called him from the car and asked to meet him at the hardware store. I arrived just in time for another ‘awakening’ and told him I wouldn’t be able to join him that day.

I sat in the car. Since my last post I’ve started to actually talk to friends about my struggle with getting a leg that fits. But I didn’t want a friend. I didn’t want empathy. I was interested in someone who might actually be able to help in a meaningful way. So I called up Jon, my last prosthetist in Canada.

Here’s the thing about my prosthetists. There have only been a few of them, but I have spent days with all of them. And days and days and days with the most recent three – Jon, and then with the two in Australia. They become friends, and the good ones become incredibly invested.

So I call Jon, and he picks up after the third ring. He’s read my blog post and hears the strain in my voice immediately. He tells me to come to Calgary and he’ll have a go. He tells me to not worry, we’ll get it sorted.

A few hours later, I call my current prosthetist to let him know my plan. It’s not an easy conversation. I explain that it is not about him, that I have to go to someone who’s been able to make it all work before. I explain that if Jon fails, then I’ll know that it’s me and nothing a prosthetist can fix by tinkering with the fit. I explain that if Jon can’t make things work then I’m on to the next phase – a serious life reorganisation that will require a long period of time without the need to wear a prosthetic, necessarily combined with a different source of income. I try not to think about what that might look like. Another opportunity for awakening.

I drove home and spent the evening scheming, plotting, articulating, and attempting to keep my anxiety at bay. The current iteration of the plan sees me heading to Calgary in mid-September, with the hope of writing ‘What a Difference a Leg Makes’ in a month’s time. Cross your fingers for me.

© Cathie Coward

© Cathie Coward © Cathie Coward

© Cathie Coward © Cathie Coward

© Cathie Coward © Cathie Coward

© Cathie Coward © Cathie Coward

© Cathie Coward © Cathie Coward

© Cathie Coward