Inspiring people in this world – they get pushed at me, or else I tend to get introduced to them. Over the past few years I’ve had the pleasure of meeting more than a few. Which is why I write about inspiration. Same as you, I talk about inspiration because I’ve been inspired.

Recently though, I happened to meet a guy with a humble kind of fortitude that is worth actually introducing.

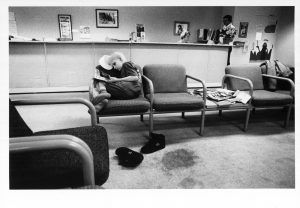

I met John through a prosthetist in Australia that I visited for an emergency joint repair. The long-term fix required the welding of little bits of metal into the joints. The prosthetist turned to me and said “I could do this for you, but the thing is there’s a guy who lives not far from you who could probably do it better”, as he passed along the guy’s phone number.

I rang up John totally out of the blue, and he invited me out to his home-based industrial workshop. From what I gather, John is a jack-of-all industrial trades and design kinda guy, but without the engineering degree. His workshop is massive and full of all kinds of cool-looking stuff I can’t identify. From my perspective all that matters is that he’s got a TIG welder and he knows how to use it. The shop also contains a number of high-end racing motorcycles and the trailer to haul them around in.

John was in a motorcycle accident involving a car 12 years ago. He broke his back, hips, pelvis, and legs. His right leg was fractured in six places. As he recounted, “they told me I would never walk again, when all they really needed to do was take me right leg off” [under-the-breath chuckle]. They did take his right leg off, quite high above where his right knee would have been.

For the record, he walks. He also works in industry. He asked me if my leg ever hurt, and then went on to explain “…me leg only really bothers me when I’ve had a 12 hour day on a ladder”. He took a pay out after his accident. As a result all of his prosthetic expenses today come out of his own pocket. The obvious solution to this little challenge was to make his own legs. For real. Apparently John shapes his sockets by heating them up, putting them on, and bearing down on them while riding a stationary bike. Or something like that.

Some time ago, he got on a motorcycle again. He now races against ‘normals’ without wearing a prosthetic, rather attaching a platform to the right side of his motorbike to put his stump on. The brakes he moves up to the left side of the handlebars. He swims and bikes as part of his training. He was a bit under the weather the day I first met him: “You know, I’ve been celebrating the past few days because I won me last race. I’ll tell you something, it makes guys sit up and pay attention when they get beaten by a guy with one leg.” [that under-the-breath chuckle again]. His season just recently finished. John ranked second…Nationally.

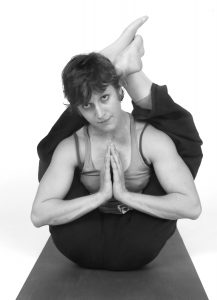

One of the best things about having 1.5 legs is that I have an excuse to call up people like John. I’ve found that most people with artificial limbs are pretty forthcoming about how they manage to do what they do, I suspect because of all the often solidary trial and error one must undertake to figure out the technical stuff. It’s a cool little unofficial club. I mean, let’s be real, the cost of membership can be pretty high. But if you happen to find yourself standing in line, waiting to enter, I would suggest seeking out the members like John.

© Cathie Coward

© Cathie Coward © Cathie Coward

© Cathie Coward © Cathie Coward

© Cathie Coward © Cathie Coward

© Cathie Coward © Cathie Coward

© Cathie Coward